Port Hope soldiers interned in Hong Kong

from The Sentinel Courier, Pilot Mound, Manitoba April 2009

(excerpted from the Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association)

Hong Kong became Canada’s greatest military blunder when she sent 1,976 untrained men the ages of Wade Wilson, Bill Treble, Mark Sloane, Owen Taylor, Derek Friesen, Danny Hildebrand, Rick McConnell, and Alain Gould to impossibly defend an allied position against 50,000 Japanese. Those who were not murdered after Hong Kong’s surrender Christmas day 1941 were forced into prison camps in Hong Kong and Japan, used as slave labour, tortured, tormented, starved and given little medical attention for four years.

When the war ended the survivors returned as different men, not speaking of their experiences except with each other. The good health they enjoyed before Hong Kong never returned. Most were tragically misunderstood the rest of their lives.

While the Japanese Government refuses to acknowledge the atrocities of their POW camps, the Canadian Government has attempted to do a little. In 1998 a settlement was paid to the remaining Hong Kong Veterans, yet nothing to the families of those who had already passed away. In 2001 another and final pension was granted – small compensation considering the after affects of being held POW - a lifetime of nightmares, ill health, emotional & physical scars and personality changes all of which also affected their wives and children.

Three Midland Regiment soldiers from Port Hope physically survived the starvation, disease, hard labour and torture in Japanese prison camps in Hong Kong and Japan: James Archibald, Frank Jiggins and Clarence Thompson

James 'Jim' Archibald

cursor over or tap the image

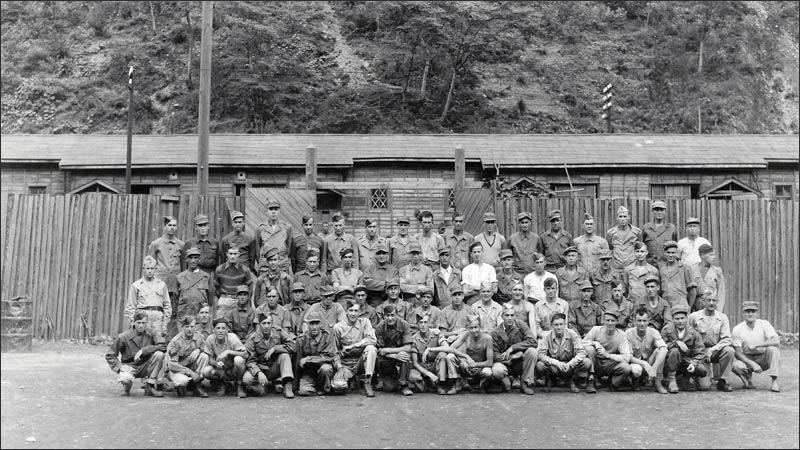

Survivors of the Battle of Hong Kong, Dec 1941, liberated from Ohashi Prison Camp in Japan Sept 15, 1945

Jim Archibald is in the back row. Also identified are George MacDonell, and Charles Richard Trick of the Winnipeg Grenadiers.

Listen to or read a Charles Trick interview here

Picture from The Memory Project

click the image to enlarge

Bruins 1947/48. Jim Archibald coached this hockey team two years after his return home from Japanese captivity

cursor over or tap a face

from the Evening Guide Friday November 9, 1984

by Kathryn Hendrick

'THERE WAS A JOB TO DO,' VETERANS SAY

Remembrance Day has long been a time of mixed emotions. We remember Canada's war veterans out of a sense of pride in their efforts and remorse for the brave individuals who fought and died to retain freedom for a whole nation. And we are appalled at the atrocity of what those brave men and women had to go through.

The sentiment this Nov. 11 is indeed a mixture of emotion in a time of cold war and worldwide unrest. A war-torn Canada is unimaginable for many of us who grew up in the years of prosperity and peace after the Second World War.

Today we are faced with the possibility of nuclear annihilation. And that possibility creates a difficult moral dilemma. Can war ever be justified?

Port Hope veterans of the two world wars were interviewed this week and asked what their attitude was toward fighting other countries which sought to overthrow weaker nations. The response was unanimous. As one veteran said:

There was a job to do and someone had to do it. A free country was too important to lose."

Many of the veterans in Port Hope feel that despite the threat of nuclear war, young Canadians would still feel the same urgency to defend their country if a call to arms were issued.

There is clearly a bond among the veterans in Canada who fought in the world wars and Korea. As John Herron, a veteran of the Second World War, said, " You remember the good times you shared together and block out the bad."

Yet the bad times also united soldiers in a time filled with suffering, death, and constant fear.

Herron was injured during the invasion of Sicily on July 23, 1943. He was put on a Red Cross hospital ship that carried ailing soldiers of all nations to a hospital in Tripoli.

There was no prejudice or hatred toward an injured enemy soldier, he said. No man was any different; they were all doing a job.

"It's a funny thing," Herron said. "Only the big shots ran the war, the little people were there because they had to be there.''

And so Herron befriended a German fighter pilot lying on a stretcher beside him.

"He couldn't speak a word of English and I couldn't speak a word of German. But we still communicated with no problem," Herron said. When the ship reached Tripoli, he never saw his friend again.

Memories of the first world war are still fresh for 95-year-old Fred Tate of Port Hope. Tate was stationed in Queenstown, Ireland, known today as Cobh.

Tate operated the hydrophone, a device used to locate enemy submarines in Ireland's coastal waters.

"I'd listen for submarines, then drop a depth charge. But I never hit anything as far as I know," Tate said. The loss of merchant ships off the coast of Ireland was dreadful, he added. They were sunk by enemy submarines or by mines floating in the ocean waters. One of Tate's proud moments during the war was the sighting out at sea of a crew whose ship had been torpedoed by an enemy submarine.

Tate had received a radio message that a crew was in distress because a submarine was chasing them. The ship sent a later message that it was being closely followed and needed help.

Tate set out in a sloop with a crew of navy personnel just as another message came on the radio. "We've been hit. We're adrift in a waterlogged life raft," the voice said.

Tate and his crew covered a four-square mile area with no luck. As they were about to return to shore, Tate spotted something far off on the horizon. It was the remaining 19 survivors of the downed ship.

At Buckingham Palace on July 10, 1919, King George V presented Tate (who was already a lieutenant) a medal and announced that he was now an officer in the British Empire Navy.

But the proud moments for Tate are mixed with bitter sentiments about war in general.

"I think everyone realises that no side wins in a war. Both sides lose in in terms of life and treasure. It's only common sense."

But the threat of a German takeover was too imminent. There is at times no choice but to defend your country, he said.

"War is an utterly terrible thing," Tate said. "Everything sinful, everything dreadful is brought about by it."

Frank Jiggins of Port Hope is one of the few remaining Midland Corps veterans sent over to Japan at the beginning of the Second World War. The regiment left Canada on Nov. 16, 1941 and members were warned that they would probably have to disembark from the boat fighting with bayonets in hand.

But that proved to be false. There was no fighting because there were no ammunition supplies. On Christmas Day, Jiggins and 500 others were taken prisoner and sent to work in a coal mine outside Hong Kong.

For four years, Jiggins survived on three teacups of rice a day. He didn't have a newspaper or any reading material. He had no idea how the war in which he had fought for a short time was progressing.

One of his worst moments was the day a Japanese soldier arrived at the camp with mail for the 500 men living in the barracks. Standing in front of the prisoners, the soldier burned each letter, the only communication they had received from the outside world since surrendering. It was the last they would receive till the war ended.

When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Jiggins was down in the coal mine digging and shoveling. At 12:30 a.m., a Japanese officer came in to the mine, took a long sword out of its sheath, and held it up in front of his face.

"The Japanese have had to surrender," a translator said, "because the Americans are using gas."

Jiggins was terrified for the first time during the war that he was not going to make it home alive.

"We all thought we were going to have our heads cut off, but then the soldier said we were free to go. We had no idea what had happened."

That night, the severely malnourished prisoners began to loot nearby villages for food. A bonfire was lit using the barracks for wood and chickens were cooked over the flames.

When the prisoners were flown out on an American plane, they were taken over Hiroshima. Jiggins is emotional as he describes the scene.

"There was nothing there. Everything was grey."

(Veterans sitting next to Jiggins during the interview said pointedly that Hiroshima was not to be discussed.)

Jiggins returned home after hospitalization in the Philippines and San Fransisco weighing 89 pounds. Today he weighs 160 pounds and refuses to have rice in his home.

But despite the slow starvation experienced in Japan, Jiggins feels no animosity toward the Japanese.

"They were common fighting men like ourselves. They had rations and they did for us what they could. If they were sick and couldn't line up for rations every Monday, then they had to wait till the following week.''

What the veterans miss about wartime was the spirit of nationalism that was so strong then. Bruce Gibson, a past president of the Port Hope Royal Canadian Legion, said, "The comradeship was enjoyable, and I miss that. I met all kinds of people. We were one big family and didn't know any prejudices."

The message from the veterans was plain and clear. Canadians had to pay a price for freedom and those who sacrificed their lives for it should never be forgotten.

Frank Jiggins in St John, New Brunswick 1941

Picture from Janet (Jiggins) Ford

cursor over or tap the image

from The Toronto Star Tuesday, July 22, 1975

by Ron Lowman (in Richmond, Ont.)

HONG KONG VETERANS ARE STILL SUFFERING 30 YEARS AFTER THE WAR

Fred Chapman wasn't even 21 when he emerged from four brutal years during World War II as a prisoner of the Japanese.

Today he's 50, retired two years because of "an almost total breakdown" in health. He putters about his house in Richmond, near Ottawa, and does a little upholstering.

Aug. 14 will mark the 30th anniversary of VJ (Victory over Japan) Day.

Despite the passage of the years, Chapman still shudders when he hears the phrase "scalded cat." He once parboiled and ate one in a prison camp. "My buddy was a farmer and knew what to do," said the white-haired, white-bearded Chapman. "When you're starving, you'll eat anything."

In the prison camps, he suffered from beriberi (a disease in which inadequate diet affects the sensory nerves, with feet and fingers first to go), pellagra (another deficiency disease which causes spinal pain, digestive troubles, drying and scaling of the skin, spasms and mental disturbances), dysentery and conjunctivitis (inflammation of the eyes).

Chapman is a member of a group of ex-soldiers known as the Hong Kong Veterans' Association of Canada. About 500 people, including wives, are expected at the group's national convention which starts tomorrow in Toronto.

According to Canadian Pension Commission figures, there are only 1,106 Hong Kong survivors left. Of these, 1,023 belong to the association.

They maintain membership because theirs is a brotherhood forged in misery, tempered in suffering thousands of miles from home—and because in unity there is more muscle in the fight for higher pensions.

1,975 SET OUT

Their story began when 1,975 officers and men of the Royal Rifles of Canada, the Winnipeg Grenadiers and a brigade headquarters staff, including two nursing sisters, landed in Hong Kong on Nov. 17, 1941. With British and Indian troops, they formed a garrison 12,000 strong.

Three weeks later, after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, they struck Hong Kong. Bitter fighting lasted from Dec. 7 to Christmas Day, when the shattered defending garrison surrendered.

In the 17 days of fighting, 290 Canadians were killed, including Chapman's best friend, Ray Oakley of Midland, Ont.

In the three years and eight months of captivity that followed, in Hong Kong and on the Japanese mainland, 265 more Canadians were shot, starved or beaten to death.

Only 1,421 members of the original Canadian contingent returned home from the war. Some, Chapman among them, looked like living skeletons.

Chapman, a boy of 17 when he laid down his rifle in Hong Kong, got into the war when he and Oakley, fed up with long hours at a laundry and drycleaning establishment in Orillia, quit and hitch-hiked to the east coast.

They were enjoying a soft drink in a Sussex, N.B., restaurant when they were approached by a recruiting sergeant. To the sergeant's suggestion that they enlist, Chapman said: "Are you out of your mind?"

Oakley was eligible but insisted he wouldn't join the Royal Rifles without Chapman, who was only 15. Chapman added three birthdays and became 18.

"I don't think we were properly prepared for what happened in Hong Kong," Chapman said. 'We never had the rigorous training we should have had; there was no heavy battle drill."

During his years as a prisoner, Chapman loaded and unloaded coal on a diet of poor rice, bad potatoes, carrot tops and fish the Japanese wouldn't touch. His dysentery was monumental.

Between Jan. 1, 1942 and Aug. 23, 1943, when he was sent to Japan, Chapman was admitted to hospital 26 times. In Japan, he had dysentery almost continuously.

LONG ORDEAL

His long ordeal ended when the Americans dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, forcing Japan's surrender.

When Chapman landed at Victoria, B.C., there was a telegram informing him his mother had died at the family home, which by then was in Toronto.

From October, 1945, to June, 1946, he was in hospital at Chorley Park. Just before his release from the army, his father collapsed and died of cancer. Chapman move in with an aunt.

With a Grade 10 education and not much experience at anything, Chapman asked the army to give him some sort of lightadministration job. He was given one with Royal Canadian Army Service Corps at Camp Borden.

During a variety of postings he worked hard at correspondence courses for five years to upgrade education. He was rewarded with a diploma of management from the Canadian Institute of Traffic and Transportation.

Chapman was a sergeant based in Ottawa in 1962 when he switched to a civilian job with the old air transport board. Two years later he achieved civil service officer status. Two more promotions followed and he became a program administrator.

But the long hours and enthusiasm for his job proved too much for his health, and in 1973 he quit on the advice of his doctor.

According to Charles Brady of Montreal, president of the Hong Kong Veterans' Association, about 150 members have had to retire prematurely and another 150 are borderline cases. The majority of those who had to quit are receiving less than 100 percent disability pensions.

The association wants all Hong Kong veterans in early retirement because of bad health to get the full pension—$575 a month, tax free, for married men and $460 for single ones. One dependent child adds $60 to a pension; two children, $104, and three, $138.

Chapman is one of the more fortunate Hong Kong veterans: His tax-free pension is 85 per cent, or $489 a month. He also receives superannuation for his 32½ years of public service, which brings his monthly total up to $1,130.

He and his wife, Dorothy, have three children: twins Judy and Stephen, 26, both married, and Alan, 20, attending Algonquin Community College.

It's expected in Ottawa that the government will accept a recent recommendation from the standing committee on veterans' affairs to change the pension formula for former prisoners of the Japanese.

The last change, in 1971, decreed that all would receive at least a 50 per cent pension. It also provided that if a veteran died, his widow would automatically receive $345 a month, and double the normal rate for each child.

The pensions are hooked to the consumer price index and rise with it. Last year, the increase was 10.1 per cent.

The anomaly of the 1971 change was that it gave large increases to men with minor injuries but nothing to the seriously disabled former prisoner who already was getting 50 percent or more.

The latest recommendation from the Commons committee would provide a minimum of 50 per cent pension and add an assessed disability payment.

Under that formula, Chapman's pension would automatically go to 100 per cent.

Murray Forman, deputy chairman of the Canada Pension Commission, recalls that immediately after World War II, Hong Kong veterans were treated like any other ex-prisoners of war.

Then it was realized they were suffering from avitaminosis (lack of vitamins) and the government began to consider them more as a group than as individuals.

By 1948, because of tropical diseases the government didn't know much about, "we were giving fairly generous pension assessments," Forman says. "Because of residual effects on the heart and possible psychological problems, we were giving 40, 50 and up to 100 per cent in some cases."

COVER INTANGIBLES

A study in the 1960s by Dr. H. J. Richardson, chief medical adviser to the commission, to determine the effects of avitaminosis, convinced the commission it should increase pensions to cover "intangibles."

The change came in 1971 but was slow to be implemented because the commission was used to dealing with set figures, such as 3 per cent ($17.25) for the loss of a little finger; 5 for the right finger; 10 for the index finger; 60 per cent for a hand ($270); 90 per cent for a leg up to the hip joint.

Putting a price on what the association called "premature aging" and forced retirement was something new. But the association kept chipping away.

A breakthrough came last year with the testimony of Dr. Albert Haas to the Commons committee. Haas, a survivor of Hitler's concentration camps, now director of a cardio-pulmonary laboratory and chest rehabilitation unit at New York University Medical Centre, cited a French law that gives every former camp inmate a 100 per cent disability pension.

In Germany, he said, if the probability is 51 per cent that a citizen's disability was contracted in the camps, it is recognised for pension purposes.

Haas' studies showing premature degeneration in fomer camp inmates was confirmed by U.S. social security statistics. While most of the normal population went on social security at 65 (women at 62), most former German camp inmates began receiving chronic disability payments before the age of 60.

The doctor told the committee that the concentration camp experience "without any doubt" had some psychological effect on each man. On the average, he said, these veterans were dying five years earlier than the norm.

Forman says that if the Commons committee recommendations are accepted, only 327 of the surviving Hong Kong veterans will be left with less than 100 percent pensions.

Here, packed ready for a move to what he hopes will be a kinder climate in Cobourg, Chapman recalls the day he and a friend wandered out of Niigata camp in Japan a few days after the war ended.

"We walked slowly downtown, just looking," he said. "On a corner, a young Japanese came up to us and said in impeccable Engish: 'Are you chaps lost?'

"Then I believed it was all over."

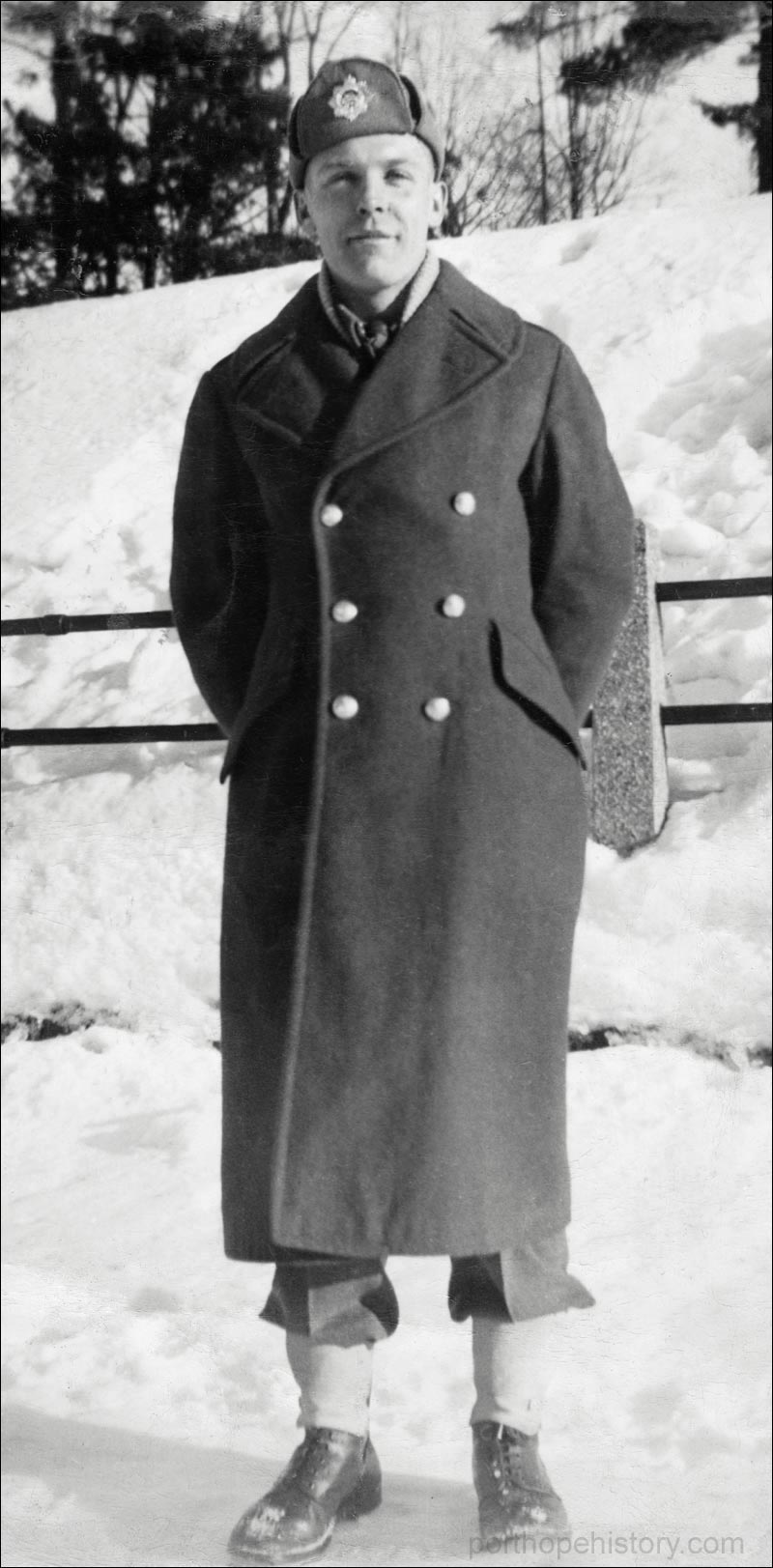

Clarence Thompson in Ottawa, Ontario 1941

Picture from Norma (Smith) Wallace

cursor over or tap the image