Picturesque Port Hope 1894

(A part of the Clifford Calvin 'Cal' Clayton collection)from the 'Picturesque Canada Series' Vol 1, No. XXIX, Sept. 24th, 1894 & No. XXX, Oct. 1st, 1894

There were three outposts of this

Kenté MissionThe Kenté (Quinte) Mission—In 1668, Claude Trouvé and François de Fénelon, Sulpician priests from France, established this mission to serve Iroquois Indians on the north shore of Lake Ontario. Kenté, the Cayuga Village which had requested the missionaries, became the mission's centre. Buildings were erected at this village, which was probably located in the Consecon area, and livestock was brought from Ville-Marie (Montreal). Under Abbé Trouvé's direction, various resident Sulpicians served the mission, but from 1675 their activities were largely confined to the village centre.

An early outpost of French influence in the lower Great Lakes region, the mission was abandoned in 1680 as a result of the moving of the Cayugas, heavy maintenance costs, and the growth of Fort Frontenac as a major post.

: the Seneca village on Frenchman's Bay already noticed; Ganeraské, the Indian village on the future site of Port Hope; and Ganneious, the Iroquois representative of our Napanee.An early outpost of French influence in the lower Great Lakes region, the mission was abandoned in 1680 as a result of the moving of the Cayugas, heavy maintenance costs, and the growth of Fort Frontenac as a major post.

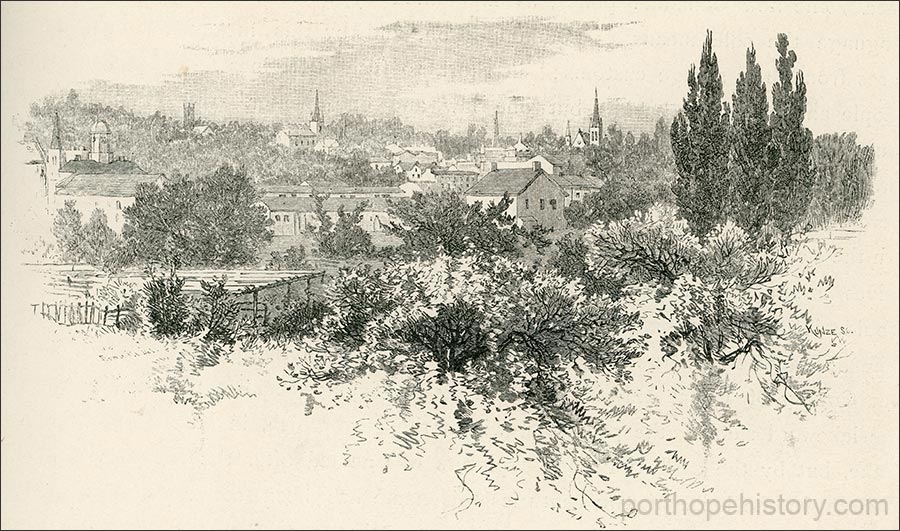

A Glimpse of Port Hope

In the spring of 1669 the

Abbé FénélonOur Canadian Abbé was not the Abbé Fénélon who wrote Télémaque and became Archbishop of Cambray; the missionary-explorer of our lakeshore was the archbishop's elder brother. They were both sons of Count Fénélon-Salignac, though by different marriages. Both bore the name of Francis, though the younger bore the addition Armand; both entered the order of St. Sulpice; and both looked wistfully to Western Canada as the Mission-Land of Promise. The younger Fénélon, being of delicate constitution, was dissuaded from following in his brother's steps and undertaking the privations and dangers of a life among the Northern Iroquois. While the elder brother was teaching the Indian children of our Whitby shore, the younger was teaching Louis XIV's grandson and heir apparent; while the elder was enduring more than the toils of Ulysses, the younger was inditing the Adventures of Telemachus. Young Burgundy was explosive enough; but the heir of a Seneca Chief had a more volcanic temper than any prince in Christendom. François Fénelon

went down to Montreal and brought back with him as a reinforcement M. D'UrféLASCARIS D’URFÉ, FRANÇOIS-SATURNIN, Sulpician, missionary, member of a noble family from the Forez region; b. 1641 at Baugé, son of Charles-Emmanuel, Marquis d’Urfé et de Baugé, marshal of His Majesty’s camps and armies, and of Marguerite d’Allègre; d. 30 June 1701 in his château of Baugé.

M. D'Urfé

, who remained during the winter at Kenté, while Fénélon explored westward and wintered at Frenchman's Bay. Two other Sulpicians, Dollier and

Galinée, spent, it may be remembered, the same winter in the forest between the Grand River and Long Point; they thankfully contrast the mildness of their season with its excessive rigour elsewhere. In Central and Eastern Canada the winter of 1669-70 was of unprecedented length and severity. June found the ground still frozen in the gardens of Montreal, and all the orchard trees dead. Unlike the tribes across the lake, who kept droves of swine, and stored up maize in large granaries, these Northern Iroquois had seemingly laid up nothing for winter. The missionaries were forced to range the forest for food, thankful for a squirrel or chipmunk, and sometimes gnawing even the fungi that grew within the shade of the pines. Fénélon's experience by the Whitby shore must have been worse than his brethren's at Kenté, for he had no one to share his thoughts or his sufferings. He died within ten years, at the early age of thirty-eight; and it is probable that his constitution was broken by the hardships of that memorable winter.To this delicately-nurtured son of the old noblesse what an appalling change from the salons of Paris, and from the refined luxury of the ancestral castle at Perigord! He would have been either more or less than human not to have been at times profoundly depressed. And he had sacrificed so much that his rank would have ensured to him! His uncle, the Marquis de Fénélon, was a distinguished soldier and statesman; the Marquis' daughter would presently marry into the great house of Montmorency-Laval. Another marriage alliance would secure for him the influence of the great Colbert. One of his uncles was Bishop of Sarlat; his brother would become the illustrious Archbishop of Cambray; and for himself, had he but yielded to the passionate entreaties of his uncle of Sarlat, and remained at home, the highest offices in Church or State were open to his legitimate ambition! The life of these warlike Iroquois was an alternation between wild revels and absolute destitution. Even amid their savage festivities Fénélon must have felt greater loneliness and dejection than Caedmon, the poet-recluse of the older Whitby shore tells us he felt amid the pagan revels of the Norsemen.

Making Port Hope in a Storm

In the Huron-Algonquin era, this north shore was without doubt more thickly villaged than the Sulpicians found it. The Iroquois desolation had swept over it, and we learn from a letter of Laval's that only in 1665 did the conquering race begin colonization. In the earlier era there would certainly be fishing villages at Whitby, Oshawa, and Port Darlington. We feel confident that, from a very early period, grist machinery and agricultural implements were manufactured at Oshawa; though primeval machinery was no better than the Huron stump-mills figured by Champlain; while the sole agricultural implements were mattocks, fashioned from red-deer's antlers. Ages before the Bowman of 1824 settled on that hill-side, a bowman of different lineage chose for his village the winding stream and the shadowy elms. The burghers of ancient Bowmanville did not build organs and pianos; nor make luxurious furniture: delicately-pencilled sprays of hemlock served for their repose; and as for sweet symphonies, had they not the forest with its clustered organ-pines?

After Frenchman's Bay, the next easterly station of the Sulpicians was at Ganeraské. We have already been at some pains to trace the error by which, in some later French maps, the name "Teyoyagon" was marked at Port Hope, displacing "Ganeraské" the real name of the Indian village. Teyoyagon was later on discovered to be identical with Toronto; but as the former name now had shifted eastward, the latter name must follow. Thus it happens that in early conveyances covering the site of Port Hope the place is called Toronto; indeed, it was to end the confusion that this eastern Toronto was, in the official post-office list of 1817, named "Smith's Creek."

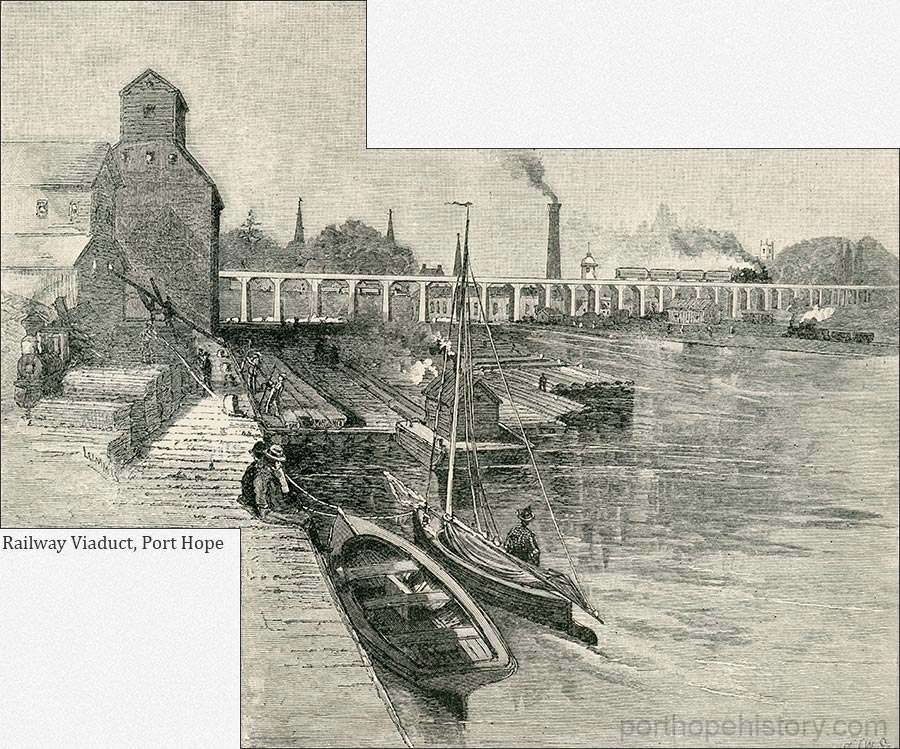

An examination of contemporary maps removes all doubt as to the correspondence of the ancient Ganersaké with the modern Port Hope. Even so lately as 1813, the mill-stream which races through the town was called in our official maps and gazetteers, Ganeraska River. But, towards the close of the last century, Peter Smith,—an honest trapper and fur-dealer,—set up his log hut by the river near the site of the great Viaduct that now carries the Grand Trunk Railway across the valley; and then Ganeraska River began to shrink and modernize into Smith's Creek. The stream now babbled night and day of Smith's fair commerce, and to the lingering shades of Indians and Sulpicians became the very River of Oblivion; even the ancient elms as they lapped of its hurrying waters forgot the past, and ceased

"repeating

Their old poetic legends to the wind."

Where the Ganeraska entered the lake there was time out of mind a natural covert whither canoes flew for shelter. Canoe-voyages are over, and now lake-birds of longer and stronger flight haunt these waters; but, if a storm breaks, it is just as it was of old: steamers and sail-craft scud and flutter towards the ancient covert. This natural gateway to the new-discovered land was not overlooked by the Sulpicians. Fénélon visited the village more than once, and acquired great influence over the Indians, which, in 1673, was turned to excellent political use by Count Frontenac.

In 1671, D'Urfé made a sojourn at Port Hope. Sometimes he would exchange places with the Superior at Kenté; and the two Sulpicians would often range the forests and neighbouring shores "chercher les brébis egarées,"—"to seek the lost sheep,"— that Laval's pastoral had so solemnly committed to their charge. In such excursions these pioneers must have become familiar with the sites on which have since arisen thriving towns and villages, and which even in pre-historic times were singled out for their natural advantages. Where the ivied tower of the Collegiate School now looks down upon Port Hope, the Sulpicians have no doubt often stood and looked out upon a waving landscape, of which the neighbouring pine-grove still whispers a reminiscence. As of old, Pine Street leads down to the harbour; but otherwise, how altered the scene! For the silence and romantic gloom of sylvan ravines, we have all the bustle and circumstance of a young city, through whose arteries is throbbing the trade of the midland lakes.

Use the form below to comment on this article. A name is required, optional email addresses will not be revealed.