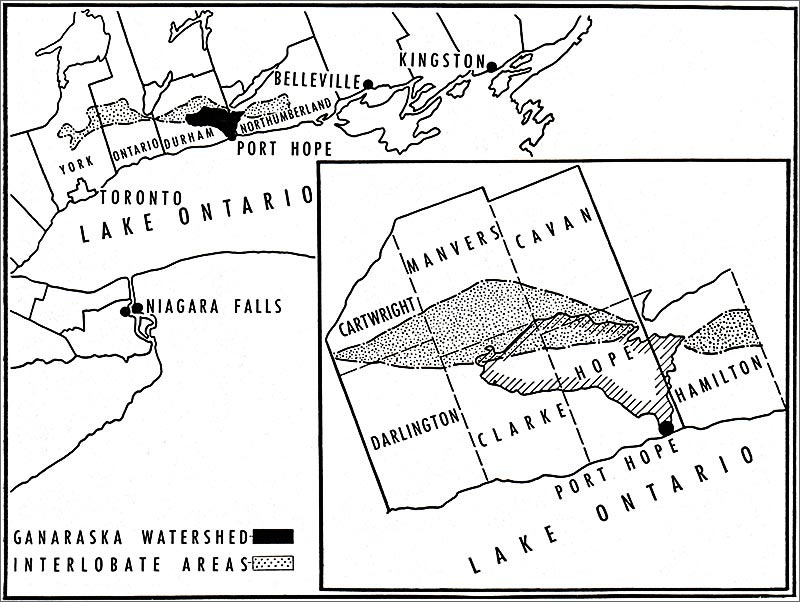

The Ganaraska Watershed

from The Ganaraska Watershed 1944

Town, Village and Rural Communities

1. INDIAN AND FRENCH PERIODS

[a] The Indian Period:

It was at the mouths of North American rivers that the red man congregated on his carrying-places and that settlements grew up. It was at the mouths of rivers that the white man usually landed and colonization began. This was true in the case of the Ganaraska.

In the days of the unwritten past, one tribe of Indians seems to have superseded another on the Ganaraska — an area of densely wooded country with varied forest growth and rolling terrain cut by multifold valleys through which the river and its tributaries flowed.

Although the discovery of a fulsom point at Rice Lake, dating from this era, indicates that Indians hunted intermittently not far from the area, evidence points to the fact that hunting in primitive times was more sporadic here than in certain other areas in Ontario.

Coming across the centuries to modern times, the earliest record of any tribe having access to this region is of the Huron which was in possession of the hunting, trapping and fishing on the north shore of Lake Ontario by the early seventeenth century.

How early in the history of the continent the secluded valley of the Ganaraska was explored by the white man cannot definitely be stated, but, prior to 1639 when the Iroquois commenced a series of raids on the Hurons, it is recorded that: "They almost destroyed the Huron Mission and rendered life so unsafe along the north shore of the lake that it was almost deserted for many years."

From the days of Champlain the Ottawa route "had been the only available approach to the interior." States C. W. Jefferys, Canadian historical painter, "Owing to the menace of the Iroquois along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario, except for short intervals of truce, the only safe route to the Huron country and the west was up the Ottawa River, and by way of Lake Nipissing, French River and Georgian Bay. Champlain in 1615, took this route to Huronia. When later in the same year he accompanied his Huron allies in their expedition against the Iroquois country at the south-east of Lake Ontario, he travelled from Lake Simcoe by the Trent valley route. On his return to Huronia, he followed the same way. Thus he twice skirted the northern boundary of the Ganaraska region, evidently without ever having penetrated it." It is thus, highly improbable that the early French explorers, or even the French, English and Dutch traders prior to the Iroquois conquest, had discovered the Ganaraska-Rice Lake carrying-route.

The Iroquois did not immediately settle in the area, even when, in 1650, "the miserable remnant of the Hurons fled northward along the western shore of Georgian Bay." They did, however, use the north shore extensively as fishing, hunting and trapping grounds from which they gathered the rich furs for the English and Dutch on the Hudson.

[b] The French Period:

Shortly after Canada had become a Royal Province of France in 1663, it seems that the French began to "find their way to Lake Ontario, to explore its shores and to lay their plans for recapturing from the Iroquois the fur-trade." The Iroquois were almost continually at war with the French, although, with the coming of the Carignan-Salieres regiment from France in 1665, some degree of peace was achieved.

At the time of the Iroquois victory, the north shore of the lake, "once so thickly peopled by the Hurons, the Petuns, and the Neutrals had been desolated; but by 1666, the Iroquois "had established themselves where the trails led off into the interior." "Beginning at the eastern end of Lake Ontario" it is recorded that Ganneious, Kenté, Kentsio, and Ganaraské had been established—these being "villages of the Cayugas who had fled from the menace of the Andastes to a securer position beyond the lakes."

In 1668 "the Sulpicians of Montreal began their mission" to these "scattered Iroquois on the north shore of Lake Ontario;" and it was they who rounded up the envoys for the Governor when Frontenac, after having founded his fort at Cataraqui (Kingston) in 1673, called together "the deputies of Ganatseqwyagon, Ganaraske, Kente, and Ganneious." On the French map of 1673, the settlement of Ganaraske is placed on the north shore of the lake near the mouth of a river which is in correct relation to Rice Lake for the present Ganaraska. This must have been near the site of the present town of Port Hope and it was marked as one of the "Villages de Iroquois dont quantite s'habituent de ce coste depuis peu." ("Villages of the Iroquois of whom numbers have been dwelling on this shore for a short time.")

How early in the years of French rule a ship's sail gleamed in the natural harbour of the Ganaraska cannot definitely be stated. It is doubtful whether La Salle himself reached this area, although the early coureur des bois did, no doubt skirt the shore and may have stopped more or less permanently in this area. Exactly when the Cayugas abandoned Ganaraske cannot be judged either, but, sometime within the next generation or two, "a race... referred to as Mississagues, in the proclamations of our Governor", settled at this point. These Indians belonged to the Algonkian family, "who were less advanced in civilization than the nations of Huron and Iroquois," the latter being "more closely related to each other than they were to the Algonquin."

The Mississauga settlement, located on the east bank of the river, was known as Cochingomink which is said to mean "the commencement of the carrying-place," and, certainly by the early eighteenth century, the Indian portage or carrying-route from the lower waters of the Ganaraska to Rice Lake was the principal approach to the interior in this vicinity.

During the last fifty years of French rule in Canada, trapping, hunting and fishing were continued by the scattered and more or less migrant inhabitants ranging the watershed of the Ganaraska. At least three other Indian posts seem to have been established within the drainage area: the first on the old carrying-route, "at about the present Dale cross-roads;" the second in Hope Township, at Doneycroft, Lot 14, Concession IV, and the third on the south end of Lot 20, Concession VII of Hope. These settlements and the more permanent village at the mouth of the river seem to have been the only Indian communities on the Ganaraska during the years when Canada was a part of the great French colonial empire.

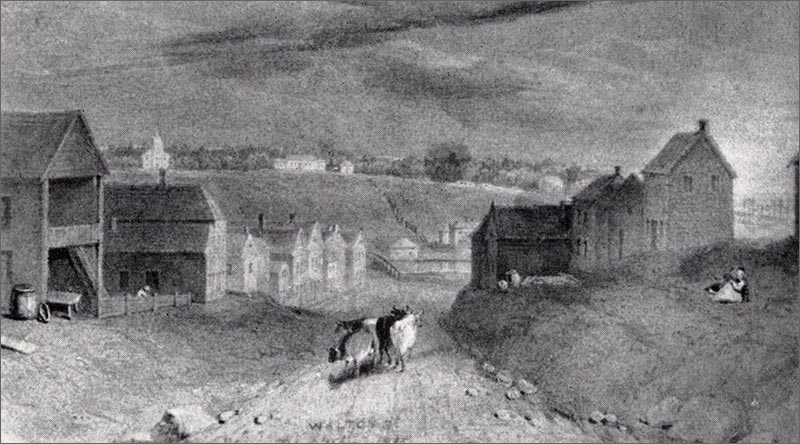

Walton Street, Port Hope, 1833

from an original watercolour by Sier

2. A PRIMITIVE ECONOMY (1759-1834)

[a] The Village of Port Hope:

With the Treaty of Paris in 1763 Canada became a British Crown Colony. Shortly after this, in 1775, the American Revolution broke out, following which there was an influx of loyalists to Canada. Some of these, it is presumed, commenced trading in the area, as authenticated by an early record in the Transactions of the Canadian Institute, for on the twenty-second of October, 1878, the following citation occurs: "Trading houses existed for some years between 1770 and 1780 at Pinewood Creek and Piminiscotyan Landing on the north shore of Lake Ontario."

A more specific reference to the early traders in this area is found in the Report of the Land Committee, where it states that: "Richard Beasely and Peter Smith, loyalists, pray for land at Toronto and at Pemitiscutiank, a place on the north shore of Lake Ontario, having already built a house at each of these places, and they petition for as many acres around each as is the usual allowance made to loyalists."

Piminiscotyan Landing, Pemitiscutiank, and its variations Pematash Wotiang Landing and Pemataskwatiang, have all been identified as the settlement at the mouth of the Ganaraska River. By 1780 it had taken its English name from the trading-post established by Peter Smyth and was called Smith's Creek.

It was not, however, until after 1788 that the British had right of access to the whole Ganaraska area. History records that: "On November 13, 1763, Sir William Johnson wrote to the Lords of Trade that the Five Nations claimed possession of Ontario, including the Mississauga country," and not until after the Indian treaty of 1788 was the land on the west bank of the Ganaraska available to the white settler.

It was the Constitutional Act in 1791, however, which gave the first real impetus to pioneering. The newly elected Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada—convening at its first session in 1792, was more active than former administrations and showed greater disposition to help settlers than had previous ones.

By October, 1792, Elias Smith, a U.E.L. merchant—who, by coincidence, had the same surname as the trader from whom the settlement took its name—and Captain Jonathan and Abraham Walton sailed as far west as the mouth of the Ganaraska and in 1793 they began engaging loyalists to settle in Hope Township. To quote from a letter written by Smith to Governor Simcoe: "Myself, with Captain Walton, brought in the country four families consisting of twenty seven Souls the 7th June, 1793, not a single family nearer on the one side of them than 60 miles on the other side 50 miles and all those people we have furnished with provision for the first year. We have an Order of Council for the Township of Hope we settled the familys on."

In 1790, Peter Smyth retired from active fur-trading and turned over his trading-post to Herchimer, also considered to have been a loyalist, and, when the pioneers arrived in early June, 1793, Herchimer was the trader in this settlement of three hundred Mississauga Indians. The settlers arriving at the mouth of the Ganaraska were Myndert Harris, the elder, Laurence Johnson, Nathaniel Ashford, James Stevens, and their families. According to a description of the arrival, authenticated by Myndert Harris, the younger: "On the 8th of June... our pioneers were landed, the men carrying their wives and children ashore, through the foaming surf that surged upon the beach.... They found the place a regular Indian village, thickly studded with wigwams and bearing the name of Cochingomink. The Indians were so startled by the unexpected approach of the pale-faces that they upbraided the latter, and denounced them as Yankee intruders, but when Mr. Herchimer explained that they were not Yankees, but children of the Great Father, the King of England, the red men became appeased, and welcomed the strangers cordially. The party reposed for the night under their tents, and in the morning began the erection of log huts, thatched with bark, on the east side of the creek.... They named the place the 'Flats'—a designation which it retained for a length of time."

Between the years 1793 and 1797, Smith and Walton—the founders of the township—settled forty families thereon and, by Order-in-Council of the eighth of October, 1797, they were given a Crown Patent for lots five, six and seven of the Broken Front and Concession one of Hope Township—this being the site of the present town of Port Hope. It was with this grant that the settlement became definitely established, took the name of Smith's Creek and village life began.

The economy of the village was agricultural, each family growing or making practically all the necessities of life. There was, however, even in the earliest years of settlement some commercial life and some import trade from the United States, although most of the supplies came through the port of Montreal. The sailing ships which plied the lake anchored off-shore and small tenders or flat bottomed boats went to shipboard, taking off passengers and supplies. Also, in 1793, Elias Smith sent his son, Peter, and a young man, named Collins, from Montreal to the settlement with a supply of goods and instructions to open a store.

The commercial part of the village lay in the valley not far back from the lake and stretched on both sides of the river. Within the first decade after its founding, Smith's Creek had a saw and grist mill, a store, a tannery, a blacksmith shop, an hotel, a distillery, and a tavern in addition to Herchimer's trading-post which had been taken over by Myndert Harris in the autumn of 1793.

The first school—a private enterprise—had been opened in the Smith homestead at the foot of the present King Street, and was taught by Collins in 1798; but the privately run school of John Farley is considered to have been the parent of the public school system of Port Hope, since the log school-house in which the classes were held had been publicly built and the scale of fees to be paid settled at meetings of free-holders in the neighbourhood. The first church meetings were held in the open or in the log houses of the settlers, and, by 1812, the village had a town hall as well as a school-house.

By 1817, the population of the village—as recorded by W. Arnot Craick—was seven hundred and fifty; and, between 1817 and 1826, it showed a marked growth. In the former year a post office was established with Charles Fothergill as the first regularly appointed postmaster. Although the post office carried the name 'Smith's Creek', previous to this time the name had fallen into disuse in legal conveyances and that of Toronto substituted. In 1819, to clear this name-confusion, a village meeting was called and the name Port Hope was unanimously accepted.

The commercial life of the village had grown appreciably during the first quarter of the new century and, by 1826, Port Hope had four general stores; two saw and grist mills; four distilleries; one malt house; three blacksmith shops; an ashery; a wool-carding factory; a rush chair-bottom factory; a cut-nail works; a tannery; a fanning mill factory; a shoemaker's shop; an hotel; three taverns; a butcher shop; a tailor shop; a watchmaker's shop; a hatter's shop; and an auctioneer's store.

Community life had also been developing rapidly and several private schools had been opened. Between 1818 and 1822, the first church—St. John's Anglican—was erected on the crest of the eastern ridge which became known about this time as Protestant Hill. Even at this time the movement of population from the valley to the spurs of the hills to the east, north-west and west of the river was noticeable; residences being built on the higher ground, especially in English Town, and on Ward's Hill.

Stage coach service was inaugurated about 1826 and with the establishment of the first newspaper in the village, the Port Hope Telegraph—published by John Vail in 1830—Port Hope may be said to have passed the stage of the rural community. In 1834, it was incorporated by act of the Legislative Assembly, its town limits defined and its name given official recognition.

(The Port Hope Telegraph was taken over by William Furby, British printer and cabinet maker, in 1831, and from this time until 1875 Furby continued to publish weekly and daily newspapers in the town.)

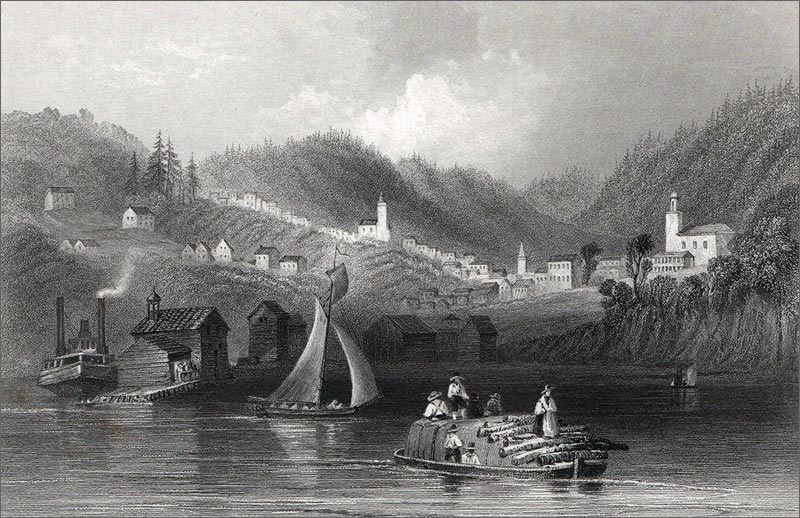

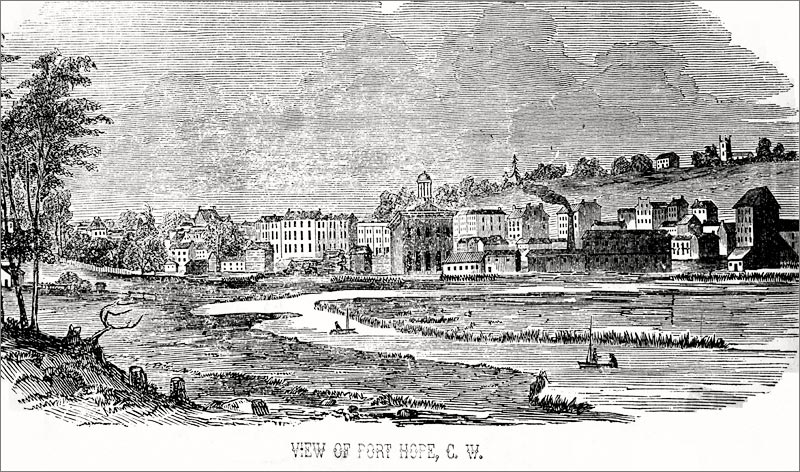

William Henry Bartlett engraving of Port Hope c1841

[b] Rural Communities.

Colonization on the Ganaraska Watershed followed rapidly after the founding of Port Hope and by the beginning of the nineteenth century at least three communities had been established north of the town. These were the villages of Dale, Welcome and Rossmount.

It seems that, from the earliest date of settlement, the villages in Hope Township were more or less dependent upon Port Hope itself, although it was not long before residents of these began to specialize in one or another of the trades necessary to life in the rural community. Moreover, British trained artisans, skilled in different trades, were attracted to the villages and it was thus that by the early eighteen hundreds, Dale and Welcome at least had grown into communities of from seven to ten families each.

DALE: The pioneers of this district were James Stevens and Jonathan and Paul Bedford. These three yeomen, with their families, began clearing and working the land in 1798 and 1799. By the time the second wave of settlement reached the watershed and from 1815 to 1820, other families had established themselves in the area and during this half decade, the first industry was commenced. Johaida Boyce, in 1818 and 1819, built a sawmill on the Ganaraska, within half a mile of the village. Thereafter it grew steadily until by 1837 the country around the village was generally opened and under cultivation.

WELCOME: Daniel Crippen, yeoman, was the original homesteader in this area. In 1797, under the Nominees of the Township, Crippen was given an original Crown Patent; while, in the following year, Leonard Soper received a military grant. Between 1805 and 1810 other families moved to Welcome, but it was with the second rush of colonization, around 1815, that the village really became generally settled.

Although Welcome does not, in the early decades, seem to have had a mill in its vicinity, it had the first waggon shop on the river north of Port Hope. This was built by John Westlake in 1830. By 1837 Welcome had a tavern at which the stage coach horses were changed, and was one of the most thriving farming communities in the district.

ROSSMOUNT: Settlement, spreading from the lake front, reached as far north as the sixth concession by 1798, and the village of Rossmount (formerly Lancaster) grew up on the boundary between Durham and Northumberland Counties. Its first settler was Cornelius Daily, a yeoman, who received military lands in 1798; while, two years later, Elizabeth Summers, as the daughter of a U. E. Loyalist, was given an original grant. It was half way to Bloomfield (Bailieboro) and about an hour out of Port Hope with a good trotter. No industries seem to have developed in Rossmount and it was soon outstripped by other communities which started up along the river.

CANTON: As early as 1801, log houses had been built on the Canton site. Centrally located in the fourth concession, it was settled when members of the families of Myndert Harris, James Hawkins and Asa Callender moved there from Port Hope. By 1810, a sprawling community had begun to develop, and there was a marked growth at the time of the war of 1812.

The village site seems particularly to have attracted millers and sawyers because of its excellent water privileges, it being situated at the mouth of the main branch of the river—the North Ganaraska—which is almost of equal size with the main Ganaraska itself. The first mill to be erected was that built by Potter in 1825 although between 1822 and 1824, three other milling families had located on farms in this part of the watershed. After 1830, three more millwrights and carpenters came to the district and the first grist mill to have been built north of Choate's Pond was that on the Potter site at Canton. It was the forerunner of the present Durham Mills and was completed by 1835.

QUAY'S: The original grant of land in this vicinity had been made to Elias Smith the younger in 1798, but it appears that it remained in its wild state until 1816 when John Perry and John Farley, yeomen, got transfers of the land and settled thereon. By 1820, other settlers followed, among whom were Thomas Quay from whom the community took its name.

Although the fifth concession line seems to have been the most northerly point of village settlement in Hope Township before 1820, the decades of the 'twenties and 'thirties saw great changes taking place between the fifth and the eighth concession lines. And by 1825, hamlets were taking shape in the vicinity of Osaca, Perrytown, Garden Hill and Elizabethville.

OSACA: During the immigration of the 'twenties and early 'thirties, several families moved to Osaca—the earliest settlers of the village being considered to be James Elliott, Robert Watson and William Goslin.

In coming to this area, the pioneers travelled northward from Orono in Clarke, followed up the township line to Concession five of Hope, and cut across to the twenty-eighth lot. The community, however, was not compactly settled and would not have been considered a village in the pioneer period. It had no industries or businesses in this era, and was dependent upon other villages for its supplies.

PERRYTOWN: On the other hand, quite a settlement had grown up by the early 'twenties on the West Gravel and seventh concession line. This site had been originally leased as a Clergy Reserve to Thomas Turner Orton in 1797, but it was John Perry (from whom the village takes its name) and Samuel Caldwell, who are considered to have been the pioneers of the district.

About the same time, Asa Callender, Robert Corbett, Aaron and Nathan Choate, and James Rutledge, settled here; while in 1821 Alexander and Archibald Morrow received land, as did W. S. Gordonier in 1826 and Alexander Ross in 1829. Thereafter, Perrytown developed and settlement spread towards Garden Hill.

GARDEN HILL: Garden Hill itself did not come into being during the pioneer period, but by 1830 there was an appreciable settlement a little east of the present Garden Hill. The community was called Adams' Corners and there was a toll gate on the West Gravel at this point at a later date. Waterpower was the incentive which brought settlers to this area. The family of Kilpatrick seems to have arrived from England in the 'twenties and to have settled in the area by the 'thirties. While there is no definite evidence when the Kilpatrick mill was built at Garden Hill it changed hands in 1841, so would be presumed to have been in operation in the 'thirties.

ELIZABETHVILLE: As in the case of Garden Hill, Elizabethville, on the Little Ganaraska, came into being because of its waterpower facilities. The pioneer of the area was Francis Tamblyn who came from England to this district in 1830, followed by three families of relatives who arrived in 1832. These were Thomas Oke, John Barkwell, and a family by the name of Hall. Shortly after the settlement of these families, newcomers arrived including John McMurtry and his wife, Elizabeth, after whom the village in 1840 took its permanent name. No mills or other industries seem to have been opened here in the 'thirties. The residents of the community, after the initial trip from Port Hope up the West Gravel, used the Clarke-Hope township line and made Orono and Bowmanville their market towns. By 1837, there was an appreciable settlement here and the men gathered in the village during the Rebellion of 1837 before marching to Port Hope to join the government troops against the insurgents.

3. EXPANSION AND DEVELOPMENT (1837-1881)

After the rebellion of 1837 and subsequent legislation, an influx of settlers into Upper Canada occurred. By this time, an era of expansion and development had been ushered in and rapid growth in village and town continued up to the eighteen eighties.

Unprecedented progress marked both Port Hope and the villages on the river between 1840 and 1850, and the population of the combined Township of Hope and the town of Port Hope doubled during this decade. From 4,000 for township and town in 1842, the figure rose to 4,600 in 1851 for the township alone, while for Port Hope itself, it was 2,300.

Generally speaking, during the period Port Hope jumped from a relatively pioneer community to an industrial centre, and the rural settlements on the watershed became the pivots about which revolved a progressive agricultural economy. During this period the output of the smithy—direct ancestor of the foundry—became more diversified; and it was at this time, also, that shingle mills, stave factories, waggon and carriage shops, cooperages, tanneries, fanning and carding mills, grist and woollen mills, and glue and candle factories began to play a vital part in the community. The export of large quantities of big timber and agricultural products, however, was the most important source of revenue within the drainage area.

[a] Port Hope:

Up to and during the eighteen-thirties, the principal source of revenue in Port Hope was its distilleries and its lumber trade—the larger proportion of its exports having been shipped to Britain through the port of Montreal. By the 'forties however, the whiskey trade had fallen off and, in its place, was more direct grain export to Britain and to the United States. The lumber business increased steadily from year to year and new mills were opened, while the town became the market town for the agricultural lands lying on the lower reaches of the river.

Particularly too, did the flour and the woollen mill business grow during these years. With the 'forties, as well, new industries in the town were opened to supply both town and villages with implements and conveyances. In 1842, Robert Chalk opened a carriage factory which supplied the local market.

In the sphere of municipal affairs, the 'forties brought considerable change; for in 1849, a new system of town government was inaugurated in Port Hope. Up until this time (from the year of its incorporation in 1834) it had been ruled by a Board of Police which met at the Exchange Coffee House on the site where the Queen's Hotel now stands. With the passing of the Municipal Institutions Act however, a board of councillors was elected to replace the Board of Police, and from these councillors a mayor was selected.

In 1853 also, came the building of the Town Hall—the first permanent municipal building since the early log building of 1812—and during this decade there were at least four papers, principally weeklies, being published in Port Hope. In 1857, the first public utility was organized—the Port Hope Gas Company—in which the town took £2,500 stock.

An event of outstanding importance over the entire watershed occurred in the 'fifties. The arrival of the 'iron horse' as it was termed, marked the real opening of the industrial era and revolutionized commercial life on the Ganaraska more than any other single occurrence to date. In 1852, Hope Township took £15,000 stock in the Port Hope, Peterborough and Lindsay Railway Company, later called the Midland and Millbrook Branch.

Port Hope, after the building of the railroads, became more than ever the market town for the newly opened country to the north. Domestic output in practically every line of industry leapt during the 'fifties and 'sixties. In 1860, the corporation withdrew from the United Counties, and its population, estimated at 2,300 in 1851, had jumped to 4,162 in 1861 and to 4,500 in 1865-67.

Apart from railroad construction and industrial expansion in the 'fifties and 'sixties, a great many harbour improvements had been made, but facilities were still inadequate. However, in 1867, the contract for the new harbour construction was let and the Dominion Government, at a cost of upwards of a quarter of a million dollars, built the Port Hope west pier and docks.

During the remainder of the 'sixties and the 'seventies, the town continued to expand and to grow more prosperous. The boom occasioned by the harbour building and the railway construction continued, and shipment of lumber and of grain—the chief commodities exported from the area—increased from year to year. In 1881 its population reached the all-time high of 5,585 and the town was looked upon as a coming metropolis.

[b] Villages on the Watershed:

As in the case of Port Hope, the small settlements on the river enjoyed a period of unprecedented prosperity from the 'forties to the 'eighties. Several communities had, by 1860, become established from the second to the eighth concession lines of Hope Township, and of these at least seven had sprung into being after 1840. They were Hastingsville, Welcome, Canton, Upper Canton, Perrytown, Adams' Corners, Choate's Mills, Dale, Davidson's Corners, Rossmount, Quay's Crossing and Knoxville. Also, between Osaca and Elizabethville, the village of Decker Hollow grew up near the township line, and Campbellcroft, which was originally known as Garden Hill Station, became an important shipping point.

Many of the villages had developed specific industries peculiar to them and thus received custom from other districts along the river. For example, Dale had the Basset Cider Mill and the Boyce Woollen Mill; Welcome was the site of the Brownscombe Pottery Works and of the Welcome Carriage Factory, and Perrytown had a soap and candle industry and carriage shops; Quay's and Knoxville had mills, while Davidson's Corners had a chair factory and Upper Canton manufactured chopping-bowls from elm.

All along the river, the principal development occurred between 1860 and 1880, when most of the villages doubled their population. With the exception of Rossmount, which seems to have had little or no industry at any time, they were all thriving milling or factory centres. Garden Hill—which as Waterford had grown up in the 'forties— absorbed Adams' Corners, and this joint settlement became the most thriving village in Hope Township by 1870. It was the business centre on the middle stretches of the river, and alone supported five sawmills, two grist mills, and the largest woollen mill on the river, as well as a pump factory.

By 1880, the population of Garden Hill was between four and five hundred, and its rate of growth had been so rapid in the twenty years previous to this that it was beginning to be looked upon as the market town for the middle and northern parts of the township. In general, this village growth may be said to have been caused by the thriving lumber business on the upper river and the lumbering operations in the northerly concessions of Hope and Clarke townships.

Prior to the 'forties, there had been no village settlement in Clarke Township on the watershed, but in the 'forties, Kendal sprang into being. Kendal, like Perrytown, Osaca, Canton, Elizabethville and Garden Hill—the other larger villages—derived its principal source of income from its milling business. In the 'forties, Theron Dickey had started a grist mill there and by the 'sixties, the village had two sawmills, two cooperages, four shingle makers, three carpenters and builders, a waggon shop, a lumber dealer, as well as a grist mill, three general stores, a drug store, a tailor's shop, an agricultural implement factory, a printer, three shoemaker's shops, a harness shop and two general blacksmith shops. By 1869, Kendal was a thriving post village, with two hotels, two churches and a school, and with a population of one hundred and fifty.

4. RETROGRESSION AND A CHANGING ECONOMY (1881-1942)

The era of decline—really under way in the township by the 'sixties—began to be felt in the 'eighties and was in full swing by 1900. The loss of the big timber trade on the lower river had occurred about 1880 while, on the upper reaches, it followed by the eighteen-nineties.

The old domestic economy had been dependent upon industries more or less indigenous to the soil, that is upon general grains and timber and manufactured articles deriving their raw materials from the forest, and upon industries producing articles for agriculture, or for domestic consumption. Generally speaking, the villages—and Port Hope as well—achieved their greatest prosperity under this economy. Two reasons for this prosperity seem to lie in the fact that they profited by the timber operations on the upper river and the increase in trade due to the putting through of the railway and the building of the harbour, both of which gave an impetus to trade with the United States. Although the big timber had been rapidly diminished in these years, it was the effect of the McKinley Tariff of November, 1890, which cut off the United States' general market and precipitated the economic depression. By this tariff duties were raised by an average of 50% on practically all commodities exported from Canada. These two factors, working in conjunction, killed industry after industry in Port Hope and village alike.

[a] Port Hope:

From 1881 to 1901 Port Hope lost steadily in population and in domestic industry and export trade. Its all-time high of 5,585 reached in 1881, had dropped in 1901 to 4,188 (its lowest figure since 1865). During the next decade, however, a slight recovery was observable, due to new industries being developed, such as the Nicholson File Factory, the Sanitary Works and other small industries.

The war of 1914-1918 did not bring any lasting stimulus to the town, and it was not until the 1930's that Port Hope again reached the five thousand mark, which is five hundred under its greatest census figure. With the establishment of radium refining by the Eldorado Gold Mines Limited in the 'thirties, and the war industry of the Second Great War era, the town is again forging ahead. Certain permanent industries, now settled there, presage that it may be able to hold its own after the war, in spite of the fact that its natural renewable resources have been exhausted or seriously impaired, and its flood hazard—which has grown in dimensions almost steadily since the 1870's—is not yet under control.

[b] The Villages on the Watershed:

The fate of the fifteen or more villages on the river followed in the main, the same sequence as that of Port Hope, although it appears that the more northerly villages did not feel the impact of the depression as early as did the more southerly settlements. But, on the other hand, the villages have not attained partial recovery as has Port Hope, since the movement from the land in the agricultural communities of the watershed has been continuous.

To-day the rural communities on the river of any appreciable size or activity are Campbellcroft, Garden Hill, Elizabethville, Kendal, Welcome and Canton. These settlements are now more in the nature of agricultural than of milling centres. The only industry carried on in them is intermittent sawing, planing, and repair work, and the cutting of chop for the farmers, while the large saw, flour and woollen mills on the river are things of the past.

Many factors have contributed to the decline of these once thriving settlements on the river. Of these, a few may be mentioned:

First: The cutting of timber from the upper slopes of the watershed and its subsequent exhaustion produced a slump in industry which could not be overcome;

Secondly: The opening up of land for agriculture at the north of the watershed was an error in land settlement since much of the soil is of low agricultural worth. When the natural 'forest manure' was exhausted, farming became increasingly difficult and led to the abandonment of the land;

Thirdly: The migration of young people from the farm to the city and the United States, and, in the last decades of the past century, to the newly opened Canadian West;

Fourthly: The loss of the pea trade through the depredations of the pea weevil, the decline in the use of horses for transport, and the effects of the McKinley tariff on export trade.

The general depression of 1929, from which the country as a whole had not completely recovered when the present war boom was ushered in in 1939, reacted on the Ganaraska; and other general causes for retrogression in rural communities had their effects within the watershed as well, although at this time there was a marked movement of population from the towns to the country. For example, mass production in industry itself killed small factories, while the automobile and the mail order house cut down the custom of the local store, thus depressing the economy as a whole.

Hence, it may be said that Port Hope and the villages lost to the large metropolis, and, through the exhaustion of the natural resources on the watershed, many of the early settlements have disappeared altogether, while those remaining are in general only skeletons of their former selves.

Use the form below to comment on this article. A name is required, optional email address will not be revealed.