|

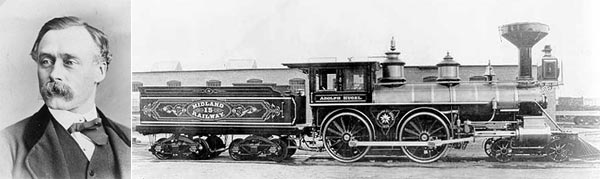

| A train passes what is now the Ganaraska Hotel and the former Walker's Undertaking business, as it heads south on Ontario Street to the Midland Station. Hold cursor over the picture for information on George H Adam. |

from the Evening Guide, (reprinted from the Lindsay Post), 1932.

RECALLS EARLY RAILWAY DAYS.

Stories that would draw a chuckle from the most solemn of men, stories of unusual happenings in the world of the 'iron horse', were related by this grand old veteran whose remarkable memory (one that still retains all of the 350 songs which, with his banjo playing, make him a popular man when the entertainment question arises) gives him authority as a veritable mine of information, and whose great good humour makes him a splendid subject for the interviewer. His railroad career started in 1876 he said. "I was working out of Port Hope, the town where I was born. My first job was as a water-boy on a ballast train putting down the road bed, and the pay was 50 cents a day, and the hours were never under 12. Of course that was pretty good pay for then." "Next year I made an advance when I got to be stake-boy on the lumber trains. I had to go along and pick up all the stakes which were taken out of the flat cars when lumber was unloaded. I had to squeeze along between the cars, and the lumber piles and throw the stakes up on the cars from both sides, and then get up and put them back in the holes ready for another load."

Next year, he said, he was still further promoted to be a brakeman, and his first trip was into Lindsay for a load of lumber. The pay on the braking job was $1.00 a day then he said. "The station then was near where the bottling works of the distillery is now, the siding where the timber from Boyd's and, other big mills was loaded, down near where the Boving is, and the tracks were very close to the river for the lumber used to be loaded right onto the cars from scows in the river."

Took Too Many Dips.

His first experience in Lindsay came near to making him quit railroading for a time, mister Adam said, for he took "rather too many dips in the Scugog to suit him. It happened this way. At that time the pin and link coupling's were in use, and the kids of Lindsay, typical "young devils", used to take the pins and links and throw them into the river. Of course this practice was later stopped by chaining the pins to the cars, but at that time every caboose carried a supply of pins and links for just such an emergency, and it was in bringing back the emergency parts that the subject of the interview almost came to grief.

"It was dark at night you know, and I had to walk along the water side of the train, carrying three or four pins and links in my arms. Of course I was hurrying, and there wasn't much room, and three or four times when I bumped my shoulder against the side of a car, I took a header into the drink. Of course I could swim like a fish, but after three or four duckings, I didn't think much of railroading. Still when I got into the van and changed my clothes, had a good hot supper, and felt the summer breezes blowing, I thought that it was a pretty good job after all."

Asked how long the engine had to stay in Lindsay he said about two hours—time enough to do the 'wooding-up' etc.

"Oh you had wood engines then did you?" he was asked. "You bet we did. Engines that had to be 'wooded up' every 10 or 15 miles. Between here and Port Hope we had to 'wood up' at Omemee, Franklin, Millbrook and Garden Hill," he said.

"What kind of wood did you burn?" "Mostly hemlock, and there was plenty of slivers to it," said mister Adam with a chuckle, probably remembering the picturesque description some fireman who had been 'slivered' gave the fuel.

|

|

Adolphus Von Hügel and the wood-burning locomotive 'Adolph Hugel' with decorated tender. Hold cursor over a picture. |

Engineers Wore White Overalls.

"How's that?" Well, it's like this, in the wood-burning days the engineer and fireman were just as clean as bank clerks. The most of them wore white overalls all the time as the wood wasn't dirty to handle. Even the oil wasn't a bad matter for them, since it was usually in the form of cakes of tallow hat were melted when they were needed. "Then, from the state of being the nattiest-looking men on the train when the wood burners were going, the engineer and fireman on the first coal burner I was with, in one hour looked just like 'niggers.' They didn't understand the coal fire, they thought they had to keep the firebox plugged full of coal just like they did with wood and what with the smoke and gas blowing into their faces when they tried to make the fire go and pawing around the coal they were a sight.

"They didn't know how to spread a fire around and one of them said on the first run, "I tell you, coal is no good. She (the engine) was never made to burn coal, she wasn't built to handle it. Of course when they got to understand... dered how they... with... wood."

O... ple... b... .

In the early days of railroading, coal burning locomotives were a thing of the future. We used to burn cord wood and had what was known as 'wooding-up' stations. Here would be piled hundreds of cords of wood. Each station had a man in charge who kept racks filled in readiness for the crew to pick up for the tender. Each rack held one cord of eighteen inch wood and as the crew piled it into the tender the man in charge took a tally that would be charged up to the particular engine.

There was great rivalry between the engineers as to which one could operate their respective engines at the least cost to the company. Many the engineer I have heard cursing his luck because he had an engine that was notoriously heavy on fuel. But there is 'more than one way to skin a cat' and I've often seen a train, on the line, at a standstill and unattended while the crew like small boys hooking apples, climbed over the fence and raided some farmer's wood pile that he had cut to sell. I have often wondered what would have happened had the said farmer been a passenger on a train when the crew took a notion to replenish the wood box. Those were wide and spacious days and I suppose the crew would have got a seat full of buckshot had that eventually happened.

Travel in the early days was more or less of a gamble and in winter time it was more so. We had no snow fighting equipment other than shovels and the strong backs of the male passengers and crew. When the trains would get stalled in a snowdrift, out would come the snow shovels and the call for volunteers. If the train was held up for any length of time, the problem of food sometimes became acute and then it was the duty of the brakeman or one of the crew to hie himself off in search of a farm house, where he would borrow a sleigh. This would be filled with provisions and after waiting until he thought that most of the snow shovelling would be done, he would drive back to the train where the passengers would be gathered around the stoves by which the cars were heated.

Braking was a risky business, particularly in freight service, we did it by hand, as air brakes had not been invented at this early date. In bad weather, such as when it was snowing or worse, sleeting, we used to put sand or ashes on the roof of the train to keep from falling off when we were moving from one car to the next. We had no foot boards, or extensions at the ends of the cars to help us from one to the other, and many times I have crawled along the top of a swaying box car, expecting each minute to find myself in the ditch.

Automatic couplers were also something held in the grip of the future and the cars were fitted up with great wooden buffers, at the end of each one, to keep them from damage while being brought together. Many an unfortunate man had his railway career cut short when he was caught between these wooden rams.

At that time our cars were coupled together by means of heavy steel hooks and chains, and it was no uncommon thing for the engine to jerk the hooks apart and leave half the train on the line. To prevent unnecessary delay when this happened we used to attach a rope to the last car and run it to the engine, where we fixed it to a bell in the cab; therefore, if the train parted, the bell would clang and warn the engineer that his train had split. Some such accidents occurred when the engineer was slowing down for a curve, and when they did the engine, released from the heavy weight of the cars, would run ahead. Naturally, the engineer would slow down for this curve and he would have the cars charging on him from the rear. When a break occurred it did not take the crew long to clamber on the roof and clamp down the brakes. Yet even these would not always hold, the locked wheels sliding along the rails carried forward by the momentum of the train. We had quite a few accidents happen this way.

Air brakes were much the same when they first replaced the old hand brakes, as coal was when it supplanted wood, he said. Of course air brakes made it easier, for in the old days there was no sitting down and watching your train brake itself as there is now, you had to get out on top whether it was raining, snowing or blowing and skin from one car to the other and hand brake 'em.

And when the change was first made, only half the train would be equipped with air brakes, he said, and the rest of the cars would be 'barefoots,' (with old hand brakes.) On long grades the 'barefoots' which were always put at the back of the train would have to be hand-braked to ease the strain, but in sudden stops the air going on on the front cars was depended upon to stop the whole train.

And on that sudden stopping, another of mister Adam's stories rests. For when those 'barefoots' jammed up to the cars which had been snubbed up by the 'air' when the engineer stopped to miss killing a cow or something on the track, it meant a grand bouncing around for those in the caboose—the last car and the one which absorbed all the shocks for the rest.

"One day," mister Adam said, "the conductor was just sitting down to his dinner in the caboose when the engineer had to stop the train in a hurry. Of course the caboose got the worst of the shock and, when everything had stopped bouncing, there was the conductor, with the meat pie he had been eating, plastered all over his shirt, and him, fit to be tied, for what he declared was a trick on the part of the engineer to do him out of his dinner."

One of the strangest sights which ever he remembered occurred around 1887, he said, when a train he was on was sent out to Victoria Junction about two miles north of the town to 'yard' the train. Through some error on some person's part this order was given at the same time as the snowplough from Lorneville was coming in on the same tracks.

"I was on top of a car and it was snowing and blowing so bad you couldn't see your hand in front of your face," mister Adam said. "And the first thing I knew there was a shock as the trains came together and I went sliding on my stomach down over three cars. Then we went to see what the damage was."

Their Engine Went Climbing.

"And here's what happened. Our engine had climbed right up the nose of the snowplough and the pilot was resting just over the cab of the other engine and the whole engine was there as solid as a dollar. The engineer on the snowplough told the fireman to get out and see what was wrong and the fireman got out into that storm and didn't think of looking up in the air, although he probably wouldn't have been able to see the engine if he had and got back in and said, "We're in an awful drift. You'll have to back up and take a run at it."

This was an authentic instance, mister Adam said, and older railroadmen, who would remember the joking the fireman got, could vouch for it, he claimed. There was even a picture taken of the two trains looked together, for when the auxiliary was called it was found to be of no use and the trains had to be towed to the 'rip track' (the repair track) and jacked apart. It was while they were on the 'rip track' that a picture of them was taken and mister Adam promised to get one of the pictures and show it to the reporter. The peculiar accident was one of those things which just happen, he said.

Another unusual experience he recalled was in the wintertime one year when it was the custom to get all the railroadmen who hadn't calls on hand and take them out in a crew to clear the road to Midland. On this particular occasion of which he spoke there were from 30 to 50 men, two engines, two cabooses and one coach, all under the direction of the roadmaster. They came to one particularly bad cut between Gamebridge and Brechlin where the snow was from eight to ten feet deep and the roadmaster saw there was no chance of getting through without help, so out piled all the men and went to work digging a series of tunnels in the cut to honeycomb the snow and make the work of the snowplough easier. "When we had done that we got back about twenty yards from the cut to watch the train, which had gone back about two miles to get a run at it, clear out the snow. And I tell, you, when that plough first hit the cut and the streams started to come from both sides of her plough it was the prettiest sight I ever saw but when the snow started to fall on us and buried us almost to the neck it didn't look nearly so I pretty."

"However the plough got through that in fine style, for in those days ploughs were heavily loaded down to keep them from bucking when they hit a heavy drift and they were driven for everything that was in them. And that sometimes made for accidents as it did this day," he said.

"When the engine had so much success with that one cut the crew decided to go at another one about a quarter of a mile down the track without having any shovelling done on it at all. So down they went full blast, but just at the start of the cut they struck some ice and the two engines went off the track into a field. Everyone got out but one fireman and no person knew where he was. They were looking in the firebox for him when I saw his face very white looking, pressed against the glass on the side of the cab. It looked as though the full weight of the engine was on him and like he was a goner for sure.

Was Saved By Snow.

"I called the other older men however and they dug him out and was as right as rain. The deep drifts of heavy snow had saved him, although he might have smothered to death if we hadn't noticed him when we did."

Of course, all through this particular story, the reporter was listening in wide-eyed wonderment,but that wasn't all there was to that trip. Oh, my no. The men had to walk six miles through the heavy snow to Beaverton the nearest shelter and one of their number 'quit' when they stopped to rest at a culvert. He didn't think he could go any further and his absence wasn't noticed till the crew got into Beaverton.

"Then," mister Adam said "the roadmaster gave two men two days pay to go back out the two miles to where he was and bring him in and when he was found we sat down to a real big dinner and believe me, we did justice to it that night."

To review mister Adam's record of his 51 years on the road, the best way to put it is to say that he has worked on all the freight, mixed and passenger trains running on this division, first as a brakeman then as a conductor.

"As a conductor mister Adam would you tell me who is the boss on the train—the engineer or the conductor?" the reporter asked him. "Well," he said, "the conductor is the boss from the pilot back and he and the engineer are jointly responsible for the safety of the train, but so long as the conductor's orders don't break any train rule they must be obeyed by every member of the train crew."

Asked if he could notice much of a difference in the amount of business handled he said he certainly could. When he first started there used to be as many as 20 to 25 crews in the freight service here and they couldn't get enough men.

"How was it they couldn't get enough men?"—"Well the work was dangerous. Every day you heard of some man getting his, fingers smashed or being hurt on the trains and it's my own opinion that if the railroads had to go back to those days of wood-burning engine's, pin and link couplings, and all the other things we had to work with, men couldn't be found who could do the work, for it was work you had to start at young to learn from the ground up."

Railroading Is Great Job.

One of the little tricks a 'brakie' had to know in those days concerned the 'reaches' used on timber trains. Timber which was too long for two cars and not long enough for three was looked after simply enough, he said. The method was to put a huge timber called a 'reach' between two cars and couple to it and let the timber from one car rest on another. That saved using an extra car and in those days cars were scarce he said.

"But when they had a wreck with a car that used 'reaches' it was a real one," he said, "and of course we had to wire the pins in when we coupled to the 'reach' for there was no fishplate on the rails in those days, just what was known as 'chairs and spikes' and the bouncing would soon have gotten rid of the pins if they hadn't been secured."

Closing the interview this veteran of the rails who lives at 81 Wislian street south with his wife with whom he hopes to celebrate 50 years of happy married life next year, 25 years of which have been spent in Lindsay, was asked by the reporter, "I guess you think railroading is a great game?"

"Oh, you bet it's a great life." he said and left this scribe with a list of other veteran railroadmen whom the same scribe only hopes are as obliging and pleasant to interview as mister Adam.

You can use the form below to comment on this article. A name is required, optional. Email addresses will not be revealed.